As we enjoy the vanilla aroma emanating from perfumes, cakes, and other desserts, we would do well to remember the genius of one child from the mid-1800s. This boy, Edmond Albius, who lived on a remote island in the Indian Ocean, against all odds created and developed a technique that would enable the quick and essentially highly profitable pollination of vanilla orchids, thus providing us with all the vanilla treats we have.

Born in Sainte-Suzanne in 1829, on the island of Bourbon (modern-day Réunion), Albius, an unschooled and illiterate 12-year-old slave, solved a botanical mystery that befuddled the greatest botanists of his day. No one before him managed to grow the plant to fruition, and his technique continues to be used to this day.

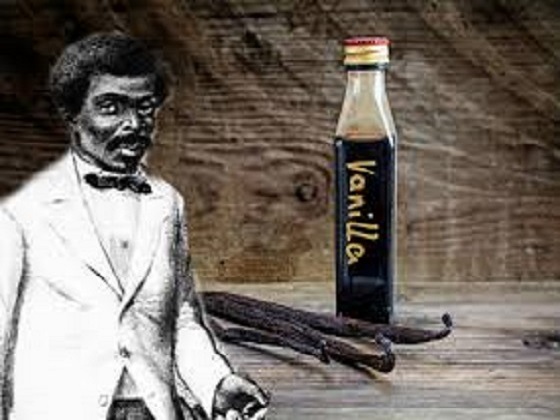

The vanilla plant is a high-climbing vine orchid with flowers, when pollinated, produce a bunch of long, stringy beans. These beans, if properly treated, give off the flavor we now associate with vanilla.

When Spanish explorers brought vanilla from Mexico, it was blended with chocolate and instantly grew to be a sensation. It was desired by kings, queens, and, pretty soon, everybody else. For instance, Madame de Pompadour, one of the great hostesses and the most famous mistress of King Louis XV, used to flavor her soups with it, or so it is said.

Portrait of Madame de Pompadour by François Boucher, 1756. Currently displayed at the Alte Pinakothek, Munich

The new sensation of the aristocracy, hailed to be a “miracle drug that could soothe the stomach” and purported to be a sensual stimulant, was in high demand. During those times, as it was being imported in very small quantities, the extract was worth as much as gold. As a result, in order to profit from the situation, people began exporting plants from Mexico to Paris and London, then on to the East Indies to see if the plant would prosper in Europe or Asia. Soon, in the 1820s, French colonists came to Réunion and nearby Mauritius with bags full of vanilla beans, hoping to start production there.

The vines, however, were sterile, because no insect would pollinate them. In Mexico, little bees were happily pollinating the plant everywhere, but here the virtuous bee was nowhere to be found near this plant. The plant indeed grew, but there was just no chance of it bearing fruit or producing the desired bean. Flowers would appear and bloom for a day, after which they would fold up and fall off. With no beans created, there could be no vanilla extract, and with that, nothing to sell.

Charles François Antoine Morren – a Belgian botanist and horticulturist, and director of the Jardin Botanique de l’Université de Liège.

Charles Morren, a professor of botany at the University of Liège in Belgium, tried to remedy this in the 1830s, by developing a method of hand-pollinating vanilla. However, due to the fact that the technique was slow, demanding too much effort, his method was never seen as a viable proposition.

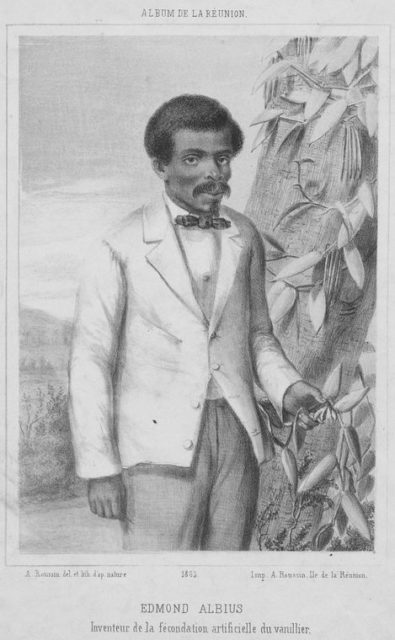

Years later, Edmond Albius would change everything. Albius, who never knew his father and whose mother died during his birth, was raised as an orphan and a slave. His fate brought him to Ferreol Bellier-Beaumont, a plantation owner on the island of Réunion, who needed help on his estate.

Edmond Albius, inventor of the artificial fertilization of vanilla

Beaumont introduced him to horticulture, and later, when he was ready, to botany. According to Beaumont, Edmond spent most of his days following him around the estate as he was tending his plants.

Among his many plants, Beaumont also owned a small surviving plantation from the time when he received a bunch of vanilla plants from the government in Paris. He planted but they had never come to produce beans.

The story goes that one particular morning in 1841, while Bellier-Beaumont was making a routine walk-around accompanied by his African slave Edmond, they came up to one surviving vine. Edmond pointed to a part of the plant showing his master two packs of vanilla beans hanging, saying he’d produced them himself, by means of hand-pollination.

Vanilla beans grown in the plantations of Kerala, India. Author, Sunil Elias, CC BY-SA 3.0

At first, as expected, Bellier-Beaumont was puzzled and asked him if he could do it again and show him how. Previously, the boy had learned to hand-pollinate a watermelon “by marrying the male and female parts together.” He explained that using this knowledge, he had done something similar to the vanilla orchids. Bellier-Beaumont was still puzzled, for he had also tried this before and failed.

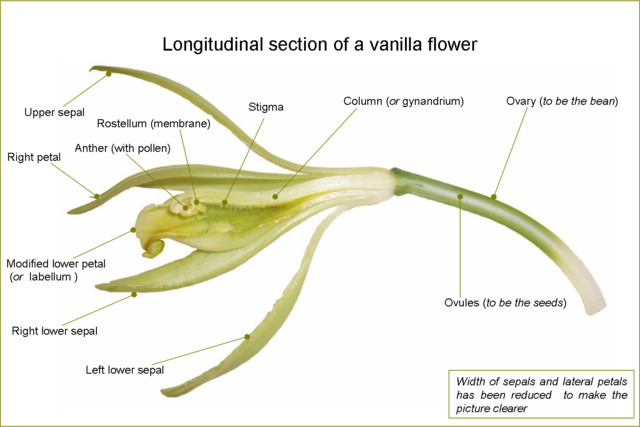

To this, Edmond told him that one day he sat down and observed the vanilla closely, looking for the part of the flower that produced pollen. He found it, but not only that, he also discovered the part that needed to be dusted, so that the plant could bear fruit. Noticing that the two reproductive parts of the flower, the male anther and the female stigma, were separated by a little lid, he lifted the flap and while holding it up, simultaneously rubbed the pollen in with a little stick. Edmond had discovered the rostellum, the lid that many orchid plants have, including the vanilla orchid, probably to keep the plant from self-fertilizing.

V. planifolia — flower. Author B.navez, CC BY-SA 3.0

This was big news and soon Edmond found himself traveling from plantation to plantation, teaching other plant owners how to fertilize their vanilla vine. In short succession, the Indian Ocean vanilla industry was born.

To draw a comparison, in 1841, Réunion exported no vanilla, although many nurtured the plant and 7 years later, they were exporting just 50 kilograms to France, whereas by 1858, two tons were being exported and by 1867, 20 tons. Near the end of the century, in 1898, Réunion exported 200 tons. By then, according to the esteemed writer and journalist Tim Ecott, “Réunion had outstripped Mexico to become the world’s largest producer of vanilla beans.”

Very soon, the word spread from Réunion and traveled to Madagascar, where French colonists used Albius’ technique to cultivate vanilla. Madagascar now stands as the world’s chief vanilla producer, and this child’s invention of manual pollination is still used today, as nearly all vanilla is pollinated by hand.

Vanilla is a major export for Madagascar, but competition from other nations is reducing its value on the world market. Here, women grade vanilla beans. Sambava, Madagascar. Author WRI Staff, CC BY 2.0

Edmond himself never prospered from his discovery, as he was a black slave child. That it was his invention was contested countlessly by all the jealous people around him who never accomplished what he had done. One botanist with a questionable reputation named Jean-Michel-Claude Richard even said that he taught the technique to a slave three or four years earlier when he was on a tour through the plantations; this was quickly declared untrue by Bellier-Beaumont, who always stuck by his “favorite child.”

Albius eventually won his freedom; not for his great contribution, but by the abolition of slavery in 1848. He never received any financial benefit from his invention that brought fortune to so many planters and as well as to the French economy as a whole, but died in miserable poverty in 1880, at the age of 51. A few weeks after he died, on August 26, 1880, a little announcement appeared in the local paper named Moniteur, which read, “The very man who at great profit to his colony, discovered how to pollinate vanilla flowers, has died in the hospital at Sainte-Suzanne. It was a destitute and miserable end.” His long-standing request for an allowance, the obituary said, “never brought a response.”